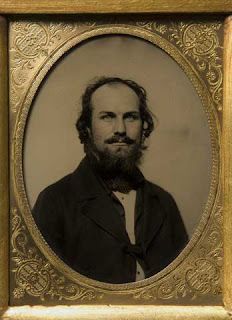

Stories Behind the Stones: Major Michael Cook (1828–1864)

In the Governor’s Reception Room of the Minnesota State Capitol, Howard Pyle’s sweeping mural The Battle of Nashville commands attention. Installed in 1906, it depicts Minnesota regiments charging across muddy cornfields toward Shy’s Hill on December 16, 1864. That day, 87 Minnesotans fell—the state’s bloodiest single day of the Civil War. Behind those brushstrokes lies the story of one man whose life and death embodied that sacrifice: Maj. Michael Cook.

Born in New Jersey in 1828, Cook was the son of Richard Cook, a War of 1812 veteran, and Nellie Louisa Courter Cook. The family later moved to New York City, where Michael trained as an architect. Restless for opportunity, he headed west in 1855 and settled in Faribault. With saw in hand, he built some of the town’s earliest homes and helped frame not only houses but also the civic foundations of a growing community. He served on the first Rice County Board of Commissioners, chaired the county’s first school district, and represented his neighbors in Minnesota’s territorial and state senate from 1857 to 1862.

In September 1862, Cook mustered into the 10th Minnesota Infantry and was soon gazetted as a major. In July 1864, he was wounded in the arm at the Battle of Tupelo. After convalescing, he rejoined his regiment, which soon faced its fiercest test: the Battle of Nashville, fought from December 14–16, 1864.

At Nashville, the 10th Minnesota was placed on the brigade’s far left—a post of distinction but grave peril. Their orders were stark: advance across 400 yards of open ground, clear stone fences, and storm Shy’s Hill while exposed to enfilade fire. Major Cook took the lead, driving his men forward into the storm.

A Confederate officer later said of the charge of the 10th Minnesota: “We opened with a fire storm of shell, canister, and musketry that some of the boys in blue said was like iron rain and terrible beyond description. We sadly decimated the ranks on the left, but powder and lead were inadequate to resist this charge.” Cook was mortally wounded in the attack on December 16. Yet the charge, carried by four Minnesota regiments, broke the Confederate line and secured one of the Union’s most decisive victories.

Cook lingered in a field hospital for eleven days before dying on December 27 at age 36. His obituary in the Faribault Central Republican mourned “another noble martyr to the cause of freedom and the union,” praising his integrity and devotion to duty. “No braver or truer man has fallen,” it declared.

In January 1865, his body was returned to Faribault and buried at Good Shepherd Cemetery. Eighteen years later, his remains were reinterred at Oak Ridge Cemetery beside his parents and brothers. To the astonishment of mourners, his body was found perfectly preserved. He was laid to rest with full military honors.

Cook’s legacy endured. In 1874, Minnesota’s Arrowhead region honored him by naming Cook County after him. A decade later, a veterans post in Faribault carried his name. Today, visitors to Oak Ridge Cemetery may pass his stone without grasping the weight it bears or the courage it represents—yet his story remains etched into the history of Rice County and into the service of a nation he gave his life to defend.

—Jeff Sauve, Northfield

With gratitude to Brian Pease, Historic Site Manager at the Minnesota State Capitol, for his invaluable assistance.